And you’re ultimately responsible for it.

In this post…

Most web designers and developers are familiar with the term PEBKAC. It stands for Problem Exists Between Keyboard And Chair and is often used to describe a bug that was triggered or caused by user error, not the application itself. Developers sometimes have a laugh at the expense of users who they feel should have taken more time to understand the application before submitting non-existent errors. And while I’ve been guilty of such thinking, I’ve come to the conclusion that it’s misguided. PEBKAC is, at its heart, an error of design, and the primary people to blame for it are not the users, but the application’s creators.

Most web designers and developers are familiar with the term PEBKAC. It stands for Problem Exists Between Keyboard And Chair and is often used to describe a bug that was triggered or caused by user error, not the application itself. Developers sometimes have a laugh at the expense of users who they feel should have taken more time to understand the application before submitting non-existent errors. And while I’ve been guilty of such thinking, I’ve come to the conclusion that it’s misguided. PEBKAC is, at its heart, an error of design, and the primary people to blame for it are not the users, but the application’s creators.

First, let me try to give you an example of PEBKAC that we can all probably relate to. Over the Christmas holiday, Randi Zuckerberg, the sister of Facebook founder and CEO Mark Zuckerberg, engaged in a very public, very messy exchange with a Twitter user who shared what was supposed to be a private picture of the Zuckerberg family enjoying the holiday. Randi assumed that the person who obtained the picture had done so by illicit means. The picture had been shared with a limited audience, and the person who released the image was not among that group.

The truth later emerged that the person who released the picture was friends with another Zuckerberg who appeared in the picture, and the picture had appeared on her Facebook news feed as part of the ordinary, normal functions of the Facebook application. The irony of all this was how the incident perfectly outlined what so many of us complain about on a regular basis: that the privacy settings on Facebook are so byzantine in their complexity that no normal person can fully comprehend them—not even the sister of the company’s founder.

The photo in question. I share Mark Zuckerberg’s skepticism of his family’s enthusiasm for Facebook Poke.

The Facebook story, with all its drama and schadenfreude, is a great example of what can happen when important, private data intersects with user error. If users can’t trust that your application will deal with your data the way they expect it to, it creates uncertainty. And given the choice between uncertainty and certainty, users will choose certainty every time. If you run a banking portal with a bill payment system, I need to be absolutely certain that if I use it to pay my mortgage, my payment will arrive where it needs to, on time, every time. This is crucially important for businesses that use software to manage their employees, finances, or projects. It’s imperative that they know what the effects of their interaction with the application will be, and that the application will never behave in a way that they don’t expect it to.

Good UX Design Requires Empathy

As the applications we use get more complex in terms of what they can do, they tend to become more complicated to use as well. User experience (UX) designers know this and use tools like confirmations, prompts, animations, visual affordances and messages to convey what effect a user’s actions will have on the application and the user’s data. Many web design conventions are so common that we no longer give any thought to how we interact with them. We know a series of ordered numbers at the bottom of a list usually indicated pagination. We know an “x” icon next to a message usually indicates that it can be dismissed.

Some things aren’t quite as straightforward to people first using your application. How can I know whether a link will perform an AJAX action or whether it will reload an entirely new page (or if it will open a page in a new tab, or in a popup)?

Which of these icons best conveys common application actions (create, view, save, delete)? If I saw any of them with no context, would it be absolutely clear to me what it does?

Destructive Actions

One of the most difficult UX challenges we deal with on Intervals concerns deleting things. I’ve found this to be true of many other applications as well.

- Will clicking an icon perform the action I expect it to (i.e. does “trash can icon” indicate that the item will be deleted)?

- Will clicking an icon prompt me to confirm my intention to delete this item?

- Once I delete this item, will there be any way to retrieve it should I change my mind?

- Will deleting this item affect other items? If so, will it tell me what those other items are? Will dependencies get resolved automatically, or do I need to do that myself?

In building Intervals, we tried to make these steps as straightforward as possible. We use a conventional “trash can” icon to indicate that an item will be deleted (most of the time with text that states as much beside it or in a hover state). In most places, we prompt users to confirm their intentions. Typically, when deleting an item cannot be undone, we offer an “archive” or “inactive” state that lets the user move the item to the background, while still maintaining that data’s integrity. Finally, Intervals has a lot of interrelated data (e.g. tasks belong to a project and are usually assigned to people), so if any other items will be affected by deleting an item, we direct users to an interstitial web page to allow them to see the whole effect of what a delete would do.

Despite all this, we still had occasional incidents where a user would submit a support request asking assistance in recovering data they had, for whatever reason, deleted — and then changed their mind. Recovering this data was particularly laborious, as altered dependencies needed to be painstakingly and meticulously restored to get as close as possible to the previous state of the data. It often involved multiple emails back and forth with the customer (sometimes across a language barrier).

We thought we had done everything correctly from a UX standpoint, but these incidents were proving otherwise. An analysis of our safeguards quickly revealed the problem: people were able to move through the delete process too quickly. They weren’t reading the warnings we had placed in the deletion process to explain the consequences of the action.

“Foistware”: Less scrupulous businesses often take advantage of a user’s haste, relying on it to get the user to consent to something the user neither wants nor needs.

Constructive Solutions

Our solution to this issue was to attempt to slow the user down whenever they were about to commit an irreversible destructive action. You’ve seen this solution many times before in other software applications. Firefox makes you wait a few seconds before you can open a file you’ve just downloaded. Apple encourages its developers to use verbs on buttons (and distinguish them visually) to force users to process what their action will do, rather than just click OK/Cancel. Hard drive partitioning software requires that users type a word to confirm that they want to delete a hard drive partition.

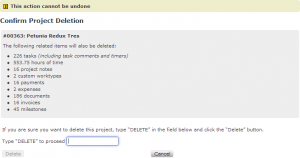

We wanted to incorporate as many of these as possible into Intervals. As a result, we redesigned our interstitial confirmation pages with the following features:

- Users are warned prominently that what they’re about to do cannot be undone.

- Users are given an explanation of all interrelated items that will be affected by a delete (and any other actions that may take place).

- Verbs are used on action buttons (rather than OK/Cancel) to tell users what will happen when they are clicked.

- Users are forced to type the word “DELETE” to confirm they want to proceed.

As you can see, deleting this item would take a lot of other data with it. This makes data recovery especially difficult.

This last step is what proved to be the most effective. It forces the user to read instructions to know how to proceed (which encourages them to read the entire warning). Additionally, it requires that a user move his or her hands from the mouse to the keyboard and back, which slows the user down to consider the consequences of a deletion and also prevents accidental or impulsive confirmations by mouse click.

The option to proceed only becomes available once the user has typed in the word “DELETE”.

Reducing User Error

It’s true that there are tons of resources out there for enhancing user experience and interaction design: heatmaps, focus groups, surveys, usability testing, and so on. But assuming you don’t have a huge budget or your own UX department, there are things you can still do. It’s often as simple as listening to and responding to your customers’ frustrations with your application. As a result of analyzing data recovery support requests in Intervals and implementing simple solutions, the number of data recovery support requests has dropped to near zero.

First and foremost, don’t disregard user error as a non-existent bug. Instead, treat it as you would any other bug. Catalog and categorize these support submissions to help you pinpoint common failure points in your software.

- Log as much as you can.

- Make it easy for users to report existing bugs and request new features.

- Look for unfinished steps in user tasks, where users began an action but didn’t finish it. This may be a sign that the steps to completion aren’t intuitive or explained sufficiently.

- Look for feature requests for features your application already has. This may be a sign that the feature is too hard to locate or needs to be featured more prominently.

- Monitor what users are saying about your software elsewhere on the internet, particularly social media and blogs.

Finally, if you make changes with the intention of reducing user error, make sure your changes are actually having that effect, and not inadvertently introducing additional complexity. For example, in the case I described above, it was very important for us to fix the deletion process without making the process so cumbersome that people would not delete anything at all.

Photo credit: Cherry Cyanide